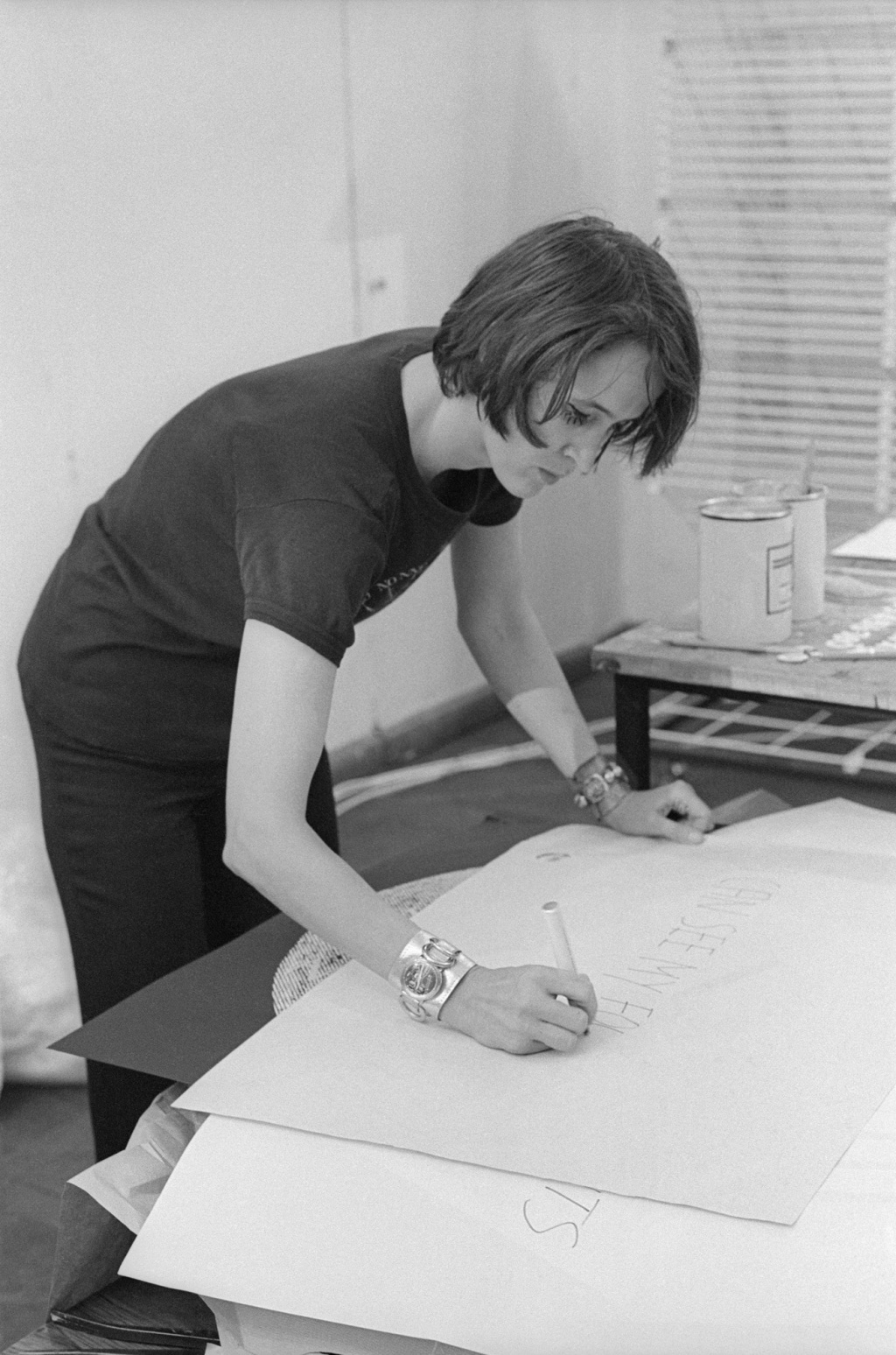

Kiki Kogelnik in her studio on 29th Street, New York, 1965

She was not Pop, she was strictly Kiki.

Tom Wesselmann, 1997

Kiki Kogelnik first visited New York in April 1961, and by September the following year she had made it her home. It was here that she found herself at the center of an embryotic Pop Art scene, yet as a non-American (who later gained American citizenship) and a woman artist simultaneously outside of it.

Kogelnik was born in Austria in 1935 and grew up in the southern town of Bleiburg. She studied art in its war-scarred capital at the Academy of Applied Arts Vienna under the sculptor Hans Knesl before enrolling at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna in 1955 to study under the painters Albert Paris Gütersloh and Herbert Boeckl. Her fellow students included Arnulf Rainer, Maria Lassnig and Hans Hollein. Her work was firmly rooted in the traditions of modernism, her paintings made with a palette of somber colors and flat painterly forms, reflective of a depressed postwar Europe. During this time, and in the years immediately after her graduation in 1958, she became an inveterate traveler. Her passport from the 1950s is filled with border control stamps as she traversed the continent from Italy to France, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Great Britain, and Ireland. Kogelnik seemed possessed by a hunger to discover a world outside her native Austria, and as she traveled, her work became looser and more intuitive. In 1959, during a visit to Paris, she met the American artists Joan Mitchell and Sam Francis, who had chosen to spend time in the city to engage in its rich artistic heritage and work alongside its ever-changing international community of makers, writers and thinkers who had similarly chosen to make an itinerant home in the city’s studios and cafés. Francis encouraged her to make the move to America and provided her with a place to live and work in his New York studio at 940 Broadway. Before relocating, Kogelnik achieved acclaim for her debut solo exhibition at Galerie St. Stephan in Vienna in October 1961. Its founder and director Monsignore Otto Mauer wrote in the accompanying catalogue about the influence of New York on her now vibrant canvases with their curvaceous fleshy forms painted in pink, orange, blue and brown that rhythmically arched the length of the canvas, where drips and runs were allowed to freely flow to their natural conclusion, and titles that were in both English and German reached out expectantly to a new life.

Kogelnik embraced New York. Initially introduced by Francis to his circle of abstract painters, critics, and dealers, she quickly established her own friendships with a new generation of artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Tom Wesselmann who would come to define American Pop Art—to which her work is often linked. But rather than a celebration of consumerism, which she found uncomfortable, her interest was elsewhere, and as restless as her very nature. Her paintings started to include the silhouettes of bodies and limbs painted in bright block colors, initially painted over former abstract works which had teetered on the suggestion of the figure, and later over grounds of silver and meshes of circles, as she imagined the promise of a new futuristic world in outer space. These utopian spaces remain haunted by the prospect of war where alongside free-floating bodies, bombs fall, satellites spy, and stylized skulls loom. The Dance with Death is an allegorical concept to be found in the history of European art and a persistant theme in Kogelnik’s work that is made ever more present by both her early life and the Cold War years of the twentieth century that followed. Kogelnik responded by looking into the body itself, proposing physical adaption and augmentation as a means of survival, leading perhaps to the hybrid body of the cyborg and ultimately the totally artificial manifestation of the robot. Through making her work since the early 60s, Kogelnik had collected an archive of silhouettes created by drawing around the prone bodies of lovers and friends in an act she called ‘taking.’ Tracing these onto flat vinyl in modern plastic colors and then cutting them out, she started to make sculptures through draping them over clothes hangers as if they had been shed and abandoned. Hung in multiples on clothing racks or augmented with similarly rendered body parts and systems, they speak of the cost of cultural and technological change.

As the 1970s dawned Kogelnik began to look more critically at the representation of women within society. Drawing on the images found within the pages of fashion magazines, she embarked on a series of paintings that portrayed their subjects as both empowered and absurd as they performed their assigned roles. Stripped of the context of a photoshoot background, dressed in fiercely patterned dresses and bathing suits and augmented by the occasional prop, their dynamic poses are contrasted with manic fixed painted faces and eyes that no longer appear to harbor any humanity. In 1974 Kogelnik made her first works in ceramics, a series of stylized freestanding women’s heads that echoed the different looks that she had adopted over the years. When reminiscing about her, Claes Oldenburg recounted how she would “be seen in the early sixties in costumes using new materials, fake fur and vinyl […which] made her into a sort of work of art.” For Kogelnik, this was a way for her to stand out and be seen, as female artists at the time tended to be overlooked and made invisible. Her paintings throughout the 70s and into the 80s continued to examine the portrayal of women: the siren, the neo-classical figure, the fool, also in combination with animals as the manifestation of desire and increasingly with accompanying simplified objects and tools. Later, these elements started to appear as sculptural forms made in ceramic.

By the early 1980s, Kogelnik had fully committed to making ceramics as part of her art practice, establishing dedicated spaces in her studios in New York and Bleiburg. This period marks a particular fluidity between her paintings, works on paper, and sculpture; an expansive cross pollination is fueled by increasing recognition and exhibiting opportunities. Echoing her earlier use of the silhouette, she made and constructed her works in ceramics using a slab technique that built and distilled a vocabulary of forms, including mask-like heads, through which she explored ideas of uniqueness and seriality, and revisited the idea of the robot, or now, as she titled them, the ‘clone.’ Other works known as Expansions brought together canvases with ceramic elements hung on the adjacent wall as if neither could be contained by the other in an endless exchange between figure and ground, object and image. Drawing was central to Kogelnik’s practice and was a place where she felt she had the greatest freedom to explore ideas, at times confessional at others simply idiosyncratic. She also created more formalized suites of works on paper such as her Robot drawings, made primarily in London in 1966, using anatomical rubber stamps whose imprints she augmented with watercolor, and Eintagsfliege (Mayfly), made in Vienna in 1983, that combined color Xeroxes of flies and spiders with painted heads and objects. In the final years of her life she started to explore the possibilities of bronze and glass, working with craftsmen to produce a series of heads and insects, sometimes in hybridized form. Despite the darkness that stalks it, her work is also characterized by a joy and humor which persisted across the decades of her life.

Kiki Kogelnik died in Vienna in 1997 where she was receiving treatment for cancer. She was 62. Since her passing, her work has been rediscovered and re-examined by a generation of artists and historians who are looking at how her art intersected with various artistic movements, especially with Pop Art, while also always standing distinctly apart. Kogelnik’s work is now regularly exhibited in North America as well as throughout Europe and is held in numerous museum collections.

Kiki Kogelnik during her Moonhappening at Galerie nächst St. Stephan, Vienna, 1969